Designing for the Senses: How Architecture and Education Meet to Create Inclusive Schools

When an architect and an educator begin talking about schools, you might expect to hear about lesson plans, floor plans and maybe the occasional budget constraint. But when Lock Pampel-Montague, a PK-12 design architect at FGMA, and Laura Karle, a school-based physical therapist, connect, the conversation shifts into a different dimension — one where sensory experiences are the starting point rather than an afterthought. For both, the meeting point is clear: design is never neutral. As Lock put it, “The space you’re in affects your ability to do things. It can help, or it can hurt — there’s no such thing as a neutral learning space.”

In the context of inclusive school design and education, the senses refer to the full range of sensory inputs — sight, sound, touch, movement and spatial awareness — that shape how students experience, process and engage with their environment.

Lizzy Scott, M. Ed., BD Manager Artcobell; Patricia Cadigan, M. Ed., ALEP, CDO Artcobell; Lock Pampel-Montague, AIA, ALEP; Celeste Karier, IIDA, ALEP, FGMA Senior Interior Designer; Laura Karle, PT, MPT, DT, OCS

The Educator in the Trenches

Laura’s career began in outpatient orthopedics, but after starting a family she pivoted to school-based physical therapy, returning to the kind of setting that had first inspired her to become a therapist. That inspiration ran deep: Her younger sister was born developmentally disabled in 1980. Her parents pursued early interventions — speech, occupational and physical therapy — and Laura, five years older, often tagged along. One day, during a school-based therapy session, her sister spoke her own name for the first time. “My mom cried, the physical therapist cried, and I realized I wanted to be a physical therapist before most of my friends even knew that job existed,” Laura recalled. “I was forever changed by the work of a woman who showed me what was possible, even when doctors said it wasn’t.”

That moment shaped the trajectory of her career. So, when she eventually transitioned from orthopedics to school-based work, it didn’t feel like a left turn; it felt like coming full circle to what had inspired her in the first place. Today, Laura works across multiple campuses in California, supporting students with significant physical and sensory needs. She sometimes steps beyond her direct caseload to help teachers rethink entire classrooms.

“I stand back and look at the classroom as a whole,” she explained. “Even if I was only there for one student, I might see something that could improve the environment for everyone.”

One of her early discoveries was that the standard “calming area” — a beanbag, some dimmed lights — often failed. “For students with high sensory needs, just sitting still wasn’t calming,” she said. “They’d already hit their capacity, and they needed movement or engagement to regulate.” She remembers one case clearly: “They’d be told, ‘Go to the calming area,’ and that was the last place they wanted to go. It turned into a battle instead of a solution.”

Working with open-minded teachers, Laura began experimenting — adding rocking chairs, movement-based activities, even crash pads. “What I would consider calming for myself might actually make things worse for another student,” she explained. “Sometimes they needed more motion, not less.”

The Architect Who Spoke Education

Lock’s story was rooted in architecture but shaped by a deep dive into education. After earning their architecture degree, they pursued a master’s in education in Finland, convinced that “school design doesn’t work unless you know how the school works.” Their focus became the marriage of architectural and educational theory, with an emphasis on data-driven, inclusive design.

Lock stresses that sensory-conscious design benefits everyone. “Things that are supportive of students with sensory needs are good for all students — and all teachers,” they said. They recalled a renovation at a Washington, D.C., charter school where acoustic panels and calming colors transformed the feel of a corridor. “They told us afterward it was night and day. Even parent-teacher nights were calmer. Everyone just felt more comfortable in the space.”

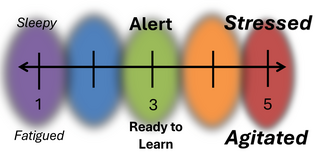

Self-Regulation Continuum

From Small Changes to Big Shifts

Laura and Lock underscore that not every improvement opportunity needs a full rebuild. Lock champions “test fits” — piloting changes in one classroom before rolling them out school-wide. “It saves money, supports teacher training, and lets you work out the kinks before scaling up,” they said.

Laura saw this in action with a single student who struggled to sit for 20 minutes. “We changed the seating and suddenly, he met the goal,” she recalled. “Teachers started talking, the principal noticed, and now we are redesigning an entire classroom as a pilot.” The plan includes a variety of seating — from bouncing stools that alert the body to rocking chairs that sooth — plus flexible layouts for different activities. “It’s not one fix for everyone,” Laura said. “It’s about having options, so each student can find what works in that moment.”

Sensory-based thinking extends beyond classrooms. Many playgrounds, Laura noted, are “technically accessible” but functionally useless for wheelchair users, especially those that feature wood chips or rubber mulch as flooring. “You could get in, but you couldn’t move. Students using wheelchairs and mobility devices ended up sitting and watching others play — and after 181 days of that, it was no fun.”

She worked with a teacher to create an obstacle course on blacktop, incorporating cones, speed bumps, tiles that squeeze colors around when you roll over them and a "car wash tunnel" for students to go through. The impact was immediate. “We came back inside and the students weren’t scratching, biting or screaming,” she said. “They were ready to learn.”

Location was another factor. Laura points out that special education classrooms are often tucked into the farthest corners of campus. “You’re taking the students with the greatest mobility challenges and making them walk the farthest. If those spaces were in the heart of the school, you’d naturally get more interaction, more belonging.”

Safety, Belonging and the Next Frontier

For both, sensory-based design boils down to two essentials: safety and inclusion. “Feeling safe and feeling included are key indicators of behavior and success in schools,” Lock said. “It’s not groundbreaking — but we still design as if it isn’t true.”

Self-regulation, they agreed, looks different for every student. “Sometimes we label a quiet, shut-down student as ‘well-behaved,’” Lock noted, “but that’s just as bad for learning as being overactive. Getting back to the middle is different depending on what’s pushing the student off balance.” Laura added, “Choice is a cornerstone of flexibility. When students can choose how to regulate, they learn to understand and manage their own needs.”

Laura’s current work even extends into juvenile court schools, where students with trauma histories often have heightened sensory needs. “It was an area we never thought to apply this work before,” she said. “But why not? If it can help them engage, it’s worth trying.”

Lock sees the next step as deepening collaboration between designers and educators. “Push your administrators to include you in design conversations,” they urged. “If you’re not at the table, your needs and the needs of your students might not be integrated — and we can’t create spaces that work without that input.”

Whether it’s a crash pad in a corner, an acoustic panel in a hallway, or a thoughtful layout that makes everyone feel welcome, sensory-based design is about more than comfort. As Laura summed it up: “Sometimes what calms a student is the opposite of what you’d expect. The key is knowing the student, knowing the options, and creating spaces where they can find their own balance.” And in Lock’s words, “We have to stop thinking of this approach as ‘special.’ It’s just good design — and when schools get it right, everyone benefits.”

News & Insights

All Articles

Boost Students’ Academic Experiences with Small Group Learning Pods