Beyond Loudest Voices: A New Blueprint for Community Engagement in Architecture

In the world of architecture and planning, community engagement has followed a simple formula — a few town halls, a public survey and a consensus-based program design process. It has been a process that favors traditional advocates, a limited amount of recreation activities, and a focus on cost-recovery with limited outside partnership involvement. But for Rich DePalma, Vice President at FGM Architects (FGMA), that traditional model, which favors the loudest voices and highest hands, is not enough.

“What we’re seeing now,” DePalma explained in a recent discussion, “is a realization that we can’t solve our problems with the same thinking and processes used to create them.” It's a nod to Einstein but also to a shift that’s been building within the field: that design equals change, and meaningful change demands more than superficial feedback.

Redefining Engagement Through Wellness

At the heart of this shift is the integration of the National Recreation and Park Association’s (NRPA) “Seven Dimensions of Wellbeing” — a framework that emphasizes emotional, environmental, intellectual, physical, social, cultural and economic wellness. DePalma sees this as the true north for architects and planners aiming to make a real difference in the communities they serve and planning processes need to adapt to enact it.

Graphic by National Recreation and Park Association: https://www.nrpa.org/our-work/partnerships/initiatives/healthy-food-access/community-wellness-hubs/

“It’s not just about building a rec facility anymore,” he said. “It’s about asking why that rec center, complex or park system master plan matters — what problems is it solving? Whose lives are we improving? Is the programming only targeting current active users who are the most vocal, is it economic focused, or is it community-focused, trying to address a wellness gap in the community and pulling in groups whose needs are normally not addressed?"

This kind of questioning is still rare, DePalma admits, but it’s starting to find footing in some planning circles. He advocates for a deeper data-informed understanding of community needs — going beyond ZIP codes to the block level, layering census data, physical and mental health metrics and local socioeconomic indicators to build a community profile — prior to engaging the public. Whether it is the policy maker, department leader, or community member; everyone’s perspective benefits from the data. Then, he suggests actively tracking engagement approaches and responsesto reveal who is heard and whose voices are missing.

The Case of Austin: Lessons are Everywhere

In his previous role on his own community’s parks and recreation board in Austin, DePalma witnessed firsthand the challenges of community engagement.

During that service, he watched the same people from the same socioeconomic backgrounds and ZIP codes driving the decisions. Though they deeply loved their park and were passionate about their preferred recreational activities, their planning approach prioritized their own experience and needs.

When dollars and space are limited, these voices drive decisions and people are left out. “At the last citywide survey, 67% of people said they were satisfied with Parks and Rec,” he recalled. “But only 25% had access to recreational programs. That’s not a win — that’s a gap.”

In the city’s long-range plan, the number one barrier to park usage was not location or safety — it was simply a lack of awareness about available programs. And that is just from a list of only 30 programs presented and not the over 120 he has since identified. And when residents were asked to prioritize future investments, responses skewed toward concerts and farmers markets — popular but not necessarily impacting those who are not benefiting from the parks and recreation system. Special needs programs and teen athletics ranked lowest.

“That was heartbreaking,” DePalma said. “We weren’t hearing from the people who actually needed the most support.”

Flipping the Script: A New Engagement Workflow

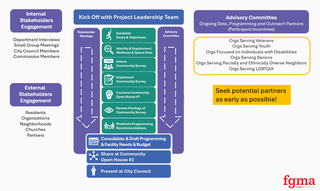

The alternative that DePalma envisions starts with intentionality. Instead of jumping straight into design, he proposes understanding the community challenges and defining the goals upfront — whether it's physical or mental health, economic development or improving access to other types of programs. From there, engagement is treated as a tool to close the gap in park and recreation satisfaction and community health while also bringing in additional resources.

This means convening advisory committees early, especially in underserved areas, and using Requests for Information (RFIs) early in the process to invite community organizations to potentially become partners. Surveys are redesigned to capture block data, health challenges, robust program interests and create an opportunity for ongoing engagement. Data is weighted to reflect the realities of underserved populations.

"We’re not just asking what people want,” DePalma emphasized. “We’re showing them what’s possible to help a community flourish."

From Awareness to Advocacy

This approach to engagement has echoes of grassroots advocacy. It’s about building trust, reaching beyond the usual suspects and making sure that community members don’t just get to comment on a plan — they help shape it.

Architects have an opportunity to become storytellers — gathering data, yes, but also weaving it into a narrative that policymakers want to understand. That’s why DePalma is pushing for broader collaboration and education, including webinars and workshops that share tools and examples from cities doing it right — from FGMA’s Pop Myles Pool project in East St. Louis, Illinois, to comprehensive wellness-centered plans in LA County and Atlanta.

For Pop Myles Pool, FGMA helped lead a deeply community-driven planning process for the redevelopment of a beloved neighborhood pool. Rather than simply updating infrastructure, the project team worked alongside residents, community leaders and youth to co-create a vision that reflected the social and cultural identity of the area. Through early advisory groups, tailored surveys and outreach that prioritized underserved voices, the plan reimagined the pool not just as a recreational amenity but as a space for wellness, inclusion and intergenerational connection. “This model became a benchmark for how thoughtful, equity-based engagement can transform a public facility into a true community asset,” said Rich.

Existing conditions at Pop Myles Pool facility in East St. Louis in January 2022 and a rendering of the renovated facility design

Designing for Impact, Not Just Aesthetics

For DePalma, community engagement is more than a phase in the design process — it’s the foundation.

“Too often, we wait for a problem to get loud before we solve it,” he said. “But if we start with real representative engagement, we can design with impact in mind from the very beginning.”

The message is clear: for architecture to truly serve the public, it has to evolve from reaction to intention — from building what’s popular to building what’s needed.

A Career Rooted in Community and Design

DePalma's journey in architecture and community engagement is marked by a blend of professional expertise and civic involvement. He joined FGMA in 2020 as a Principal with a focus on parks and recreation, public affairs and alternative funding throughout Texas.

Beyond his role at FGMA, DePalma is deeply involved in community service. He currently serves as Board President for the Barton Springs Conservancy and the Advisory Councils for Explore Austin and TreeFolks. His commitment to public service extends to his tenure as vice chair of the Parks and Recreation Board in Austin, where he had a front-row seat to the challenges and opportunities in community engagement.

News & Insights

All Articles

How City Planning, Zoning and Regulations Shape Successful Architecture Projects